Home

+

Published : 09 May 2025, 03:55 PM

Warren Buffett made his name advising devotees never to bet against the United States. Yet even Uncle Sam’s greatest fan is implicitly questioning whether the days of US outperformance are over. When he announced plans to bow out on Saturday, Buffett’s Berkshire Hathaway was less focused on America Inc than ever before, with over half of its investment portfolio in cash and its highest ever weighting to non-US assets.

Yet 48 hours later at the Milken Institute Global Conference, Scott Bessent took up Buffett’s old baton with relish, urging his audience to go all-in on the United States. The entirety of the country’s economic history, quipped the Treasury secretary, can be distilled in just five words: “Up and to the right.” In whom should investors trust: Buffett or Bessent? Is the era of US investment outperformance over – or is it here to stay?

The greenback’s recent slide raises a third possibility: both might be true at once. For domestic investors, who count their gains in dollars, US assets may continue to power ahead – even as the opposite might be true for foreigners, who are exposed to currency risk. Much like the weird world of quantum physics, where particles have no fixed position until they’re observed, the existence of US exceptionalism may increasingly depend on an investor’s perspective.

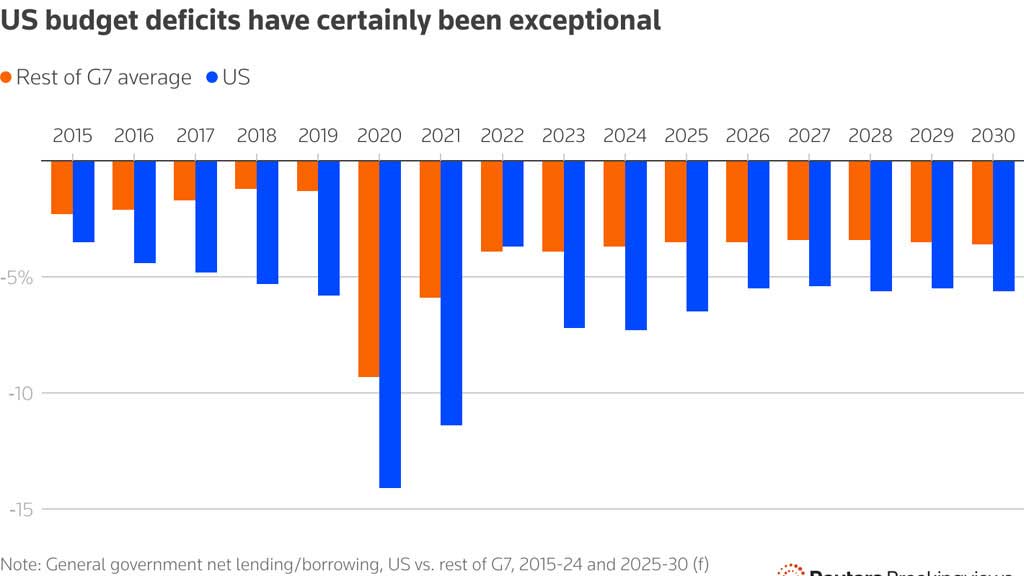

The last decade of US investment dominance has had three underlying drivers. The first was simple: unprecedented fiscal largesse. President Donald Trump’s 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act slashed levies. President Joe Biden’s 2022 Inflation Reduction Act ramped up spending. The net result was that the US budget deficit climbed from 3.5 percent of GDP in 2015 to nearly 6 percent in 2019, using the International Monetary Fund’s measure of general government net borrowing, before rebounding again to nearly 7.5 percent of GDP in 2024. At 3.7 percent, the average budget deficit of the other members of the G7 group of advanced economies was barely half the United States’s level last year.

With Trump’s second coming, austerity looks further away than ever. Congressional budget resolutions passed in early April imply massive tax cuts and relatively puny spending cuts, potentially adding $5.7 trillion to federal debt over the next decade, according to Reuters. The International Monetary Fund reckons the US deficit will still be 5.6 percent of GDP in 2028, against an average for the rest of the G7 of 3.4 percent.

Importantly for investors, the US Treasury market is unfazed: the benchmark 10-year yield is currently lower than at the beginning of the year. There’s little opposition from either policymakers or markets to keeping the US fiscal engine firing.

The next big driver of US outperformance has been its leadership in technology and artificial intelligence, exemplified by the so-called Magnificent Seven stocks – Microsoft, Apple, Nvidia, Amazon.com, Alphabet, Meta Platforms, and Tesla – which account for roughly a third of the S&P 500 Index’s market capitalisation.

The bull case for this theme is that America’s technological edge is sustainable and poised to have profound macroeconomic effects. New York University economist Nouriel Roubini argues that the US leads the rest of the world in 10 of 12 “industries of the future”, from defence to fusion energy, and that the ongoing AI investment boom will see the economy’s potential growth rate to approach 4 percent by 2030, from around 2 percent to 3 percent in recent years.

Sceptics see a bubble instead. Jim Chanos, founder of short-selling specialist Kynikos Associates, observes that while US tech capex indeed contributed nearly a full percentage point to GDP in the first quarter of 2025, the last time it did so was right before the peak of the dot-com bubble in early 2000.

In contrast to the fiscal engine, financial markets have recently been wobbling on this second theme. US equities have had a wild 2025. Tech stocks and Tesla have been particularly hit. Yet the S&P 500 has roared back from a near-20 percent drawdown in early April and is now just 4 percent below its 2024 year-end level. Faith in the Magnificent Seven may be dented – but there’s little sign yet that Uncle Sam’s tech engine has ground to an ignominious halt.

That leaves the third driver of US outperformance: the long bull market in the dollar. In the decade to March 2024, the US dollar appreciated by nearly 30 percent against the euro, for example, which improved euro-based investors' returns to investing in US financial assets by nearly 3 percentage points per year. For investors in equities, these currency gains were a nice little add-on, topping up the S&P 500’s annualised 13 percent total return in US dollars to 16 percent. For fixed-income investors, they were the major draw given that yields were languishing at multi-decade lows.

In 2025, however, this third mighty engine of US exceptionalism has gone into reverse. The United States’s net international investment liabilities have reached an all-time high of nearly 90 percent of GDP, and the net flow of income from its international assets has completely dried up. The Bank for International Settlements’ real effective exchange rate index, meanwhile, rates the greenback as about as expensive as at any time in 40 years. Combined with the White House’s open endorsement of a weaker currency, that’s resulted in a screeching handbrake turn. The DXY US Dollar Currency Index has dropped by 8 percent this year. The greenback’s sharp depreciation this week against a number of Asian currencies suggests further weakness may be on the way.

Is it worth investing in US markets even if they’re powered by only two of their three historic engines? That depends on where you sit. US assets may do just fine in dollar terms, fuelled by continued American leadership in tech and turbocharged by further fiscal boosts. For foreign investors, however, American assets will be less compelling if a bear market in the greenback leaves them racing to stand still.

Such confusing quantum states have existed for long periods before. In the half-decade leading up to April 2008, for example, the S&P 500 returned just over 13 percent annually in dollar terms – just like in the decade to 2024. But the greenback was on the skids, losing nearly a third of its value over that time. For an unhedged euro-based investor, those exceptional returns were thus cut almost in half.

Of course, US investors too can get on the right side of the trade simply by buying foreign assets. Buffett himself opined on Saturday that he “wouldn’t want to be owning anything that we thought was in a currency that was really going to hell.” That may prove a valuable parting shot from the Oracle of Omaha.